Understanding Violence

Created by Neighbours, Friends, and Families

What is gender-Based Violence?

Gender-based violence, commonly referred to by its acronym GBV, is violence that is committed against someone based on their gender identity, gender expression or perceived gender.

If you look closely, you will see the roots of GBV all around you—in the jokes that demean members of the LGBTQI2+ community, in the media messages that objectify women, and in the rigid gender norms imposed on young children.

In Canada, GBV disproportionately impacts women and girls, as well as other diverse populations such as Indigenous Peoples, LGBTQI2+ and gender non-binary individuals, those living in northern, rural, and remote communities, people with disabilities, newcomers, children and youth, and seniors.

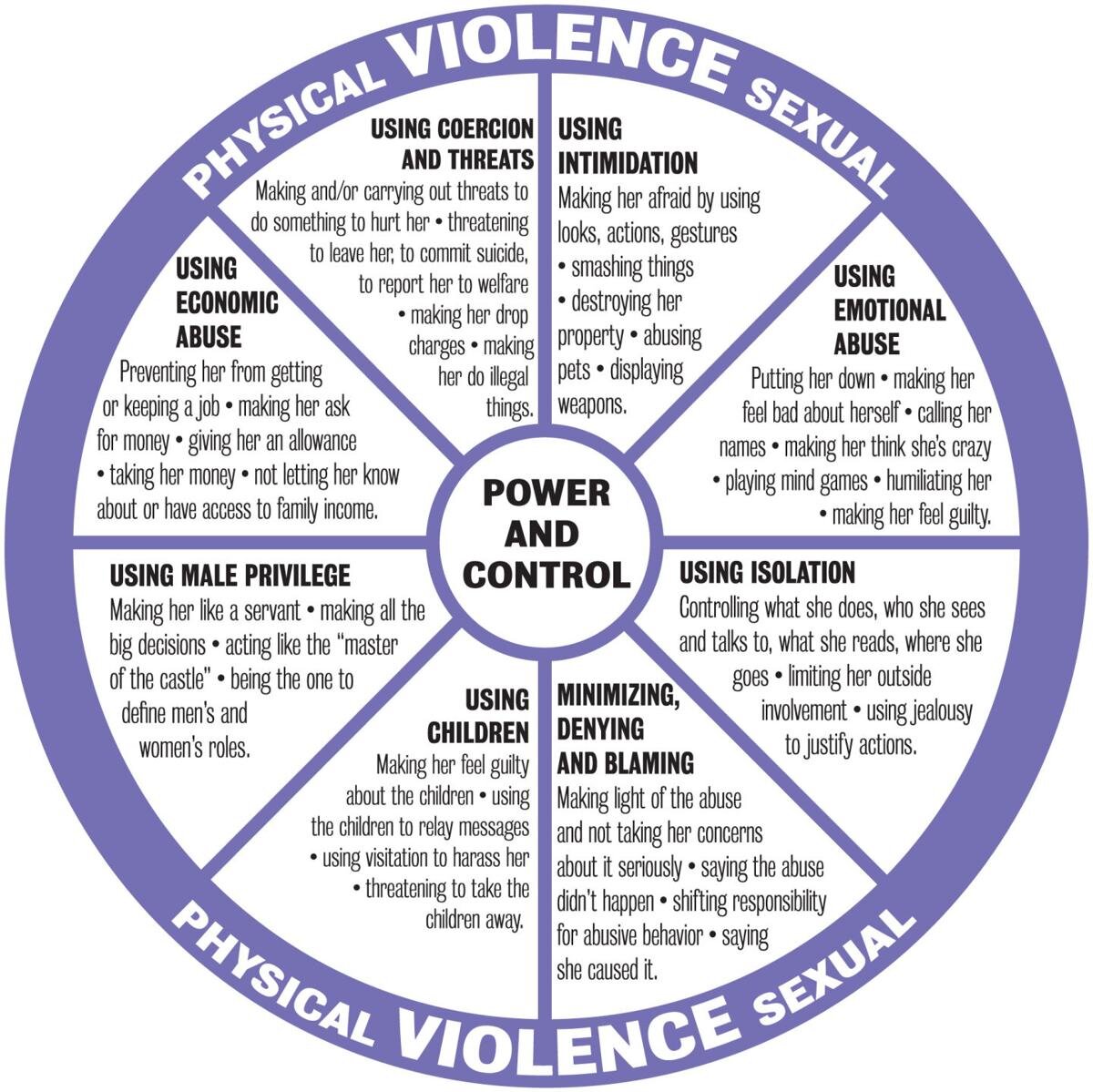

Often, the term violence is used to refer to specific, usually physical acts, while the word abuse is used to refer to a pattern of behaviour that a person uses to gain or maintain power and control over another.

GBV is not limited to physical abuse but includes words, actions, or attempts to degrade, control, humiliate, intimidate, coerce, deprive, threaten, or harm another person.

When it comes to GBV, a person may experience more than one form of violence or abuse. Here, these words are often used interchangeably, or the broader term ‘abuse’ is used.

Learn More About:

Connection between gender-based violence and fatphobia

Gaslighting as a tactic of emotional abuse

Test your knowledge!

Take the gender-based violence quiz. (Because gender-based violence is so rarely talked about, getting a low score on this quiz is normal. We created this not to shame folks about what they don’t know, but as another way for folks to learn past the myths that we’re talk about abuse, coercion, and violence.)

What is Sexual Violence?

Sexual violence is a broad term that describes any violence, physical or psychological, carried out through sexual means or by targeting sexuality.

It can include but is not limited to:

sexual abuse

sexual assault

rape, (date rape, marital rape, partner rape, stranger rape, rape where there is multiple perpetrators)

ritual abuse

sexual harassment

incest

childhood sexual abuse

stalking

indecent/ sexualized exposure

degrading sexual imagery

voyeurism

exhibitionism

sharing sexual photographs without permission

online sexual harassment

rape during armed conflict

trafficking and sexual exploitation

unwanted comments or jokes

Keep learning! Way more layers and info about dynamics of sexual violence here.

Created by YWCA Canada

Learn more about:

Created by Outside of the Shadows - Julie Lalonde and Ambivalently Yours

What is Stalking?

From SPARC (Stalking Prevention, Awareness & Resource Centre):

Stalking is pattern of behavior directed at a specific person that would cause a reasonable person to fear for the person’s safety or the safety of others; or suffer substantial emotional distress.

Stalkers use a variety of tactics, including (but not limited to): unwanted contact including phone calls, texts, and contact via social media, unwanted gifts, showing up/approaching an individual or their family/friends, monitoring, surveillance, property damage, and threats.

Stalking is typically directed at a specific person – the victim. However, stalkers often contact the victim’s family, friends and/or coworkers as part of their pattern of behavior.

Many stalkers’ behaviors seem innocuous or even desirable to outsiders – for example, sending expensive gifts. The stalker’s actions don’t seem scary and are hard to explain.

Stalking & Fear

Fear is contextual.

What’s scary to one person may not be scary to another. In stalking cases, many of the behaviors are only scary to a victim because of their relationship with the stalker.

For example: A bouquet of roses is not scary on its own. But when a victim receives a bouquet from an abusive ex-boyfriend who she recently relocated to get away from – and she did not think he knew where her new home was – this flower delivery becomes terrifying and threatening.

It is essential for responders to ask about and understand why certain behaviors are scary to the victim.

People react to stalkers in a variety of ways. Some may seem irritated or angry rather than scared, while others may minimize and dismiss their stalking as “no big deal.” Irritation, anger, and/or minimization may be masking fear.

It is helpful to consider how victims may change their behaviors to cope with the stalking. Are they changing travel routes? Avoiding certain locations? Screening calls? These may be indicators that victims are afraid.

Check out our conversation about the lies we’re taught about stalking with Julie Lalonde:

Why does violence against women happen?

Abuse doesn’t happen because of what survivors were wearing or because a survivor had a drink, abuse happens because of abusers taking advantage of the small (sometimes tiny) and large ways they have power over their victims.

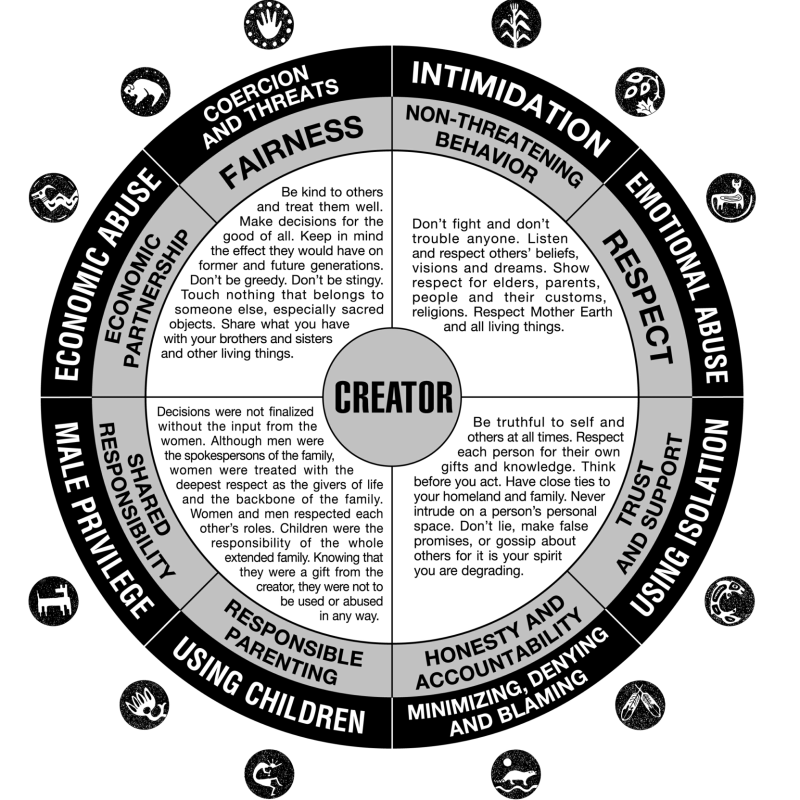

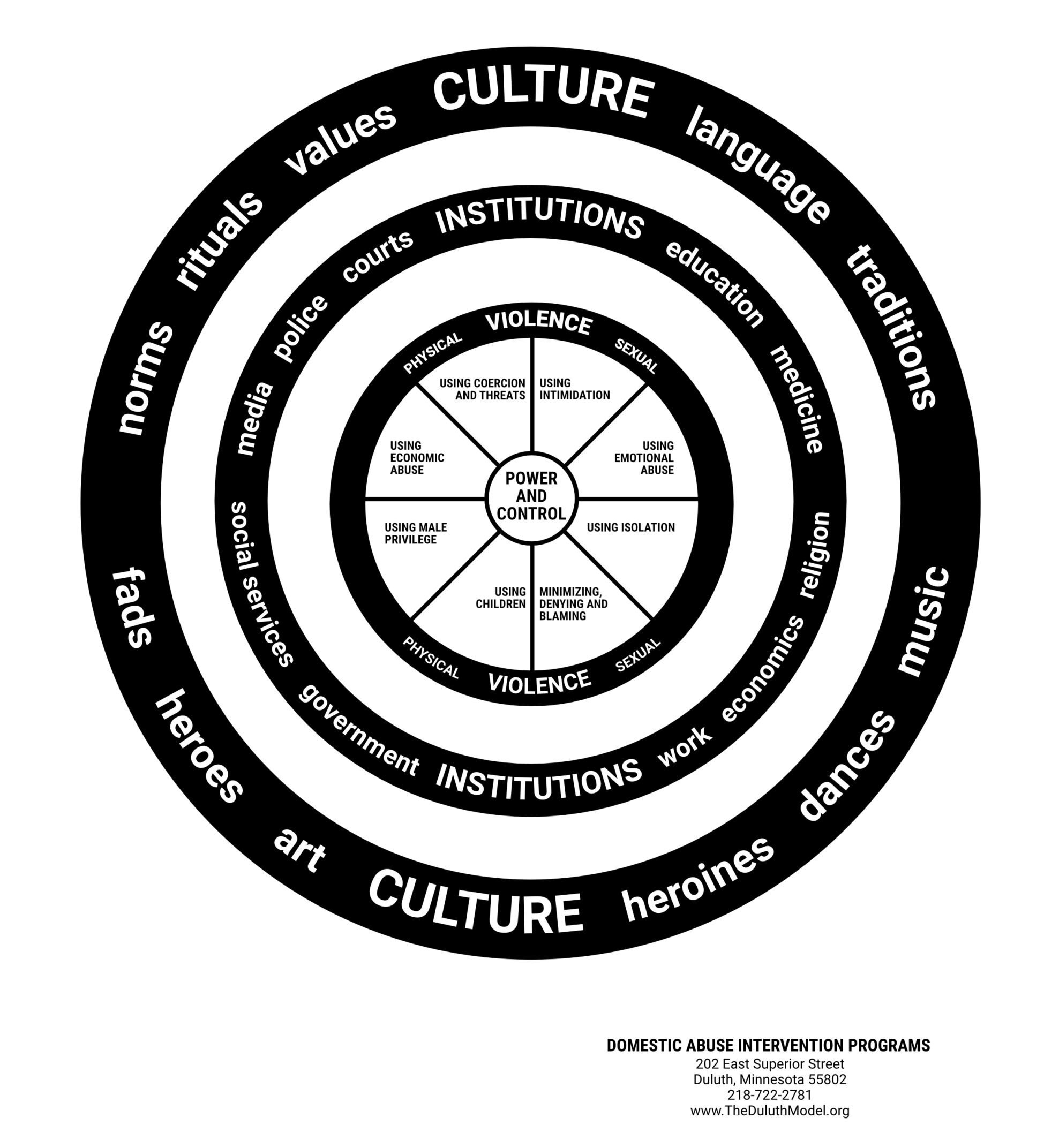

Created by the Domestic Abuse Intervention Programs, folks have adapted the Power and Control wheel to reflect intersectionality and different forms of oppression that survivors experience including:

Creator Power and Control Wheel

Culture Power and Control Wheel

Deaf Power and Control Wheel

Disabled Power and Control Wheel

Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Trans Power and Control Wheel

HIV/AIDS: Coercive Factors Wheel

Immigrant Power and Control Wheel

Incarcerated Power and Control Wheel

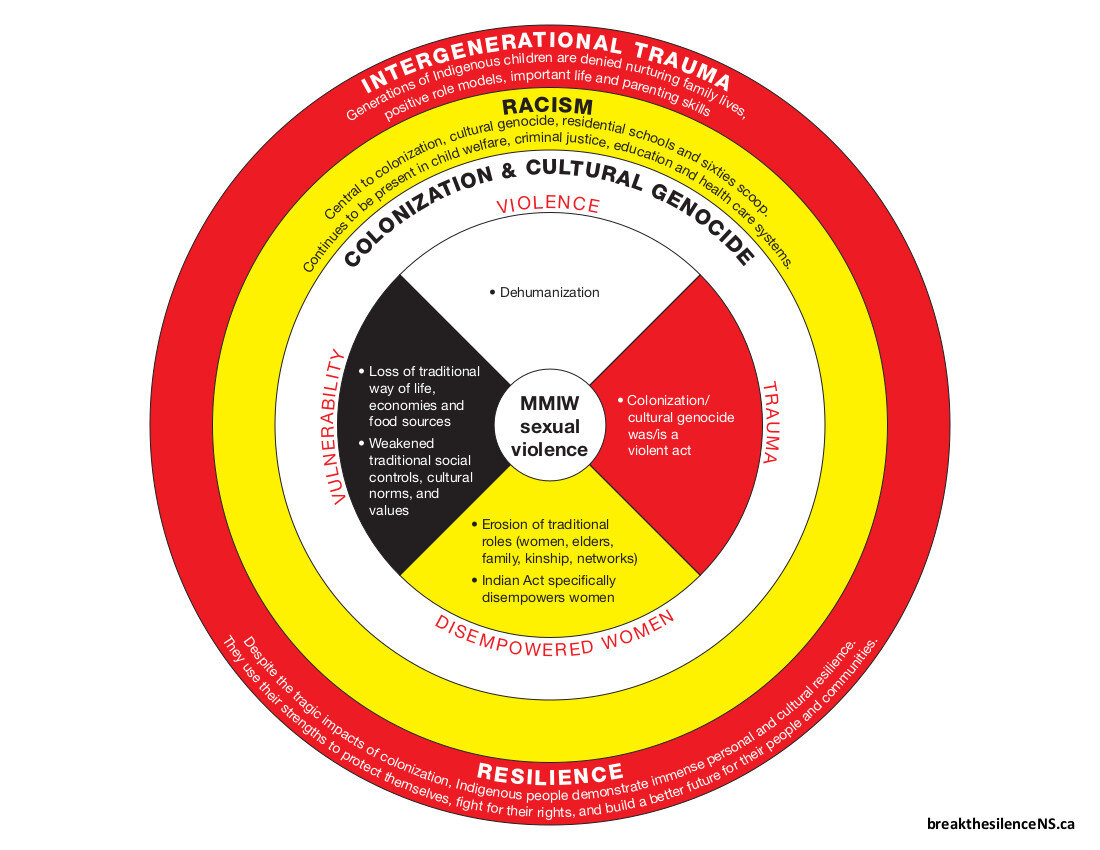

Intergenerational Trauma Wheel

Medical Power and Control Wheel

Mental Health System Power and Control Wheel

Military Power and Control Wheel

Police Perpetrated Power and Control Wheel

Teen Power and Control Wheel

Trans Power and Control Tactics

Using Animal Cruelty Power and Control Wheel

Workplace Harassment Power and Control Wheel

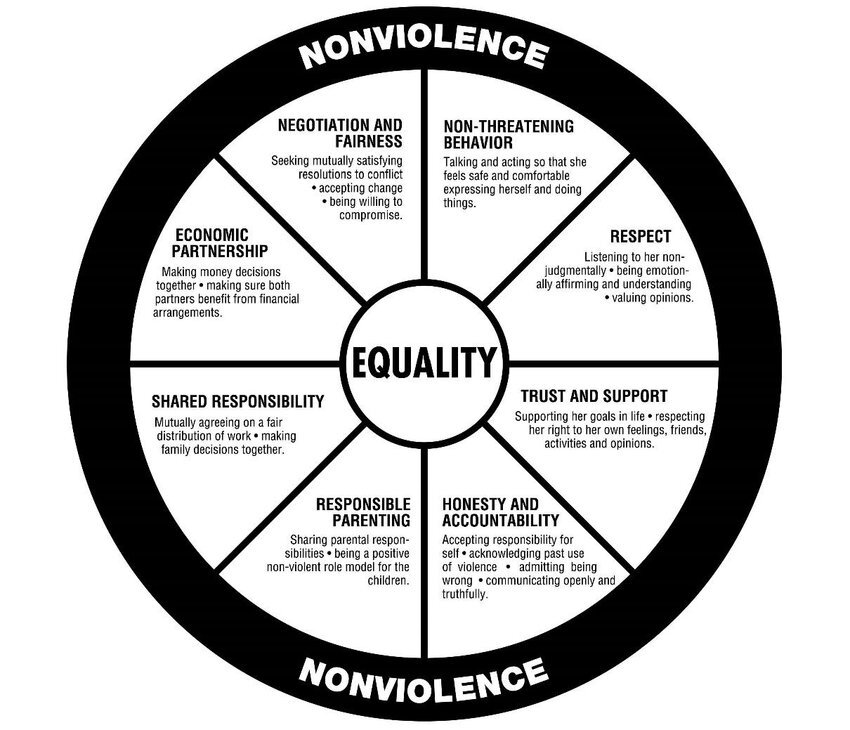

If we’re talking about abuse, it can be important to describe what respect, equity, and safety look like too. There are some good examples of infographics created to describe what healthy relationships can look like:

Respect Wheel: People with Disabilities in Partner Relationships